Art is like a living creature that evolves through time. From statements imposed by old schools to antagonistic points of view that have created a whole new spectrum of subjective movements. Art is nowadays conceived as the expression or application of human creative skill and imagination into a visual form. It is an open-minded practice that has no prejudices of any kind or form. A non-discriminatory discipline that holds no restrains. It brings a space for artists to express themselves freely. However, in the midst of this total freedom, the artist Kate Pickering states a different point of view.

Kate has agreed to meet me in the south of London, close to where she lives. We are having coffee and tea for a change. I can sense some blend of discomfort and irony in her eyes when she explains to me that this non-discriminatory aperture of art is deceiving, especially if the artist is an evangelical. “You can be as disruptive as you want to be, as long as you are not an evangelical Christian”, says Kate with an ironic smile. “That’s where the line is drawn”.

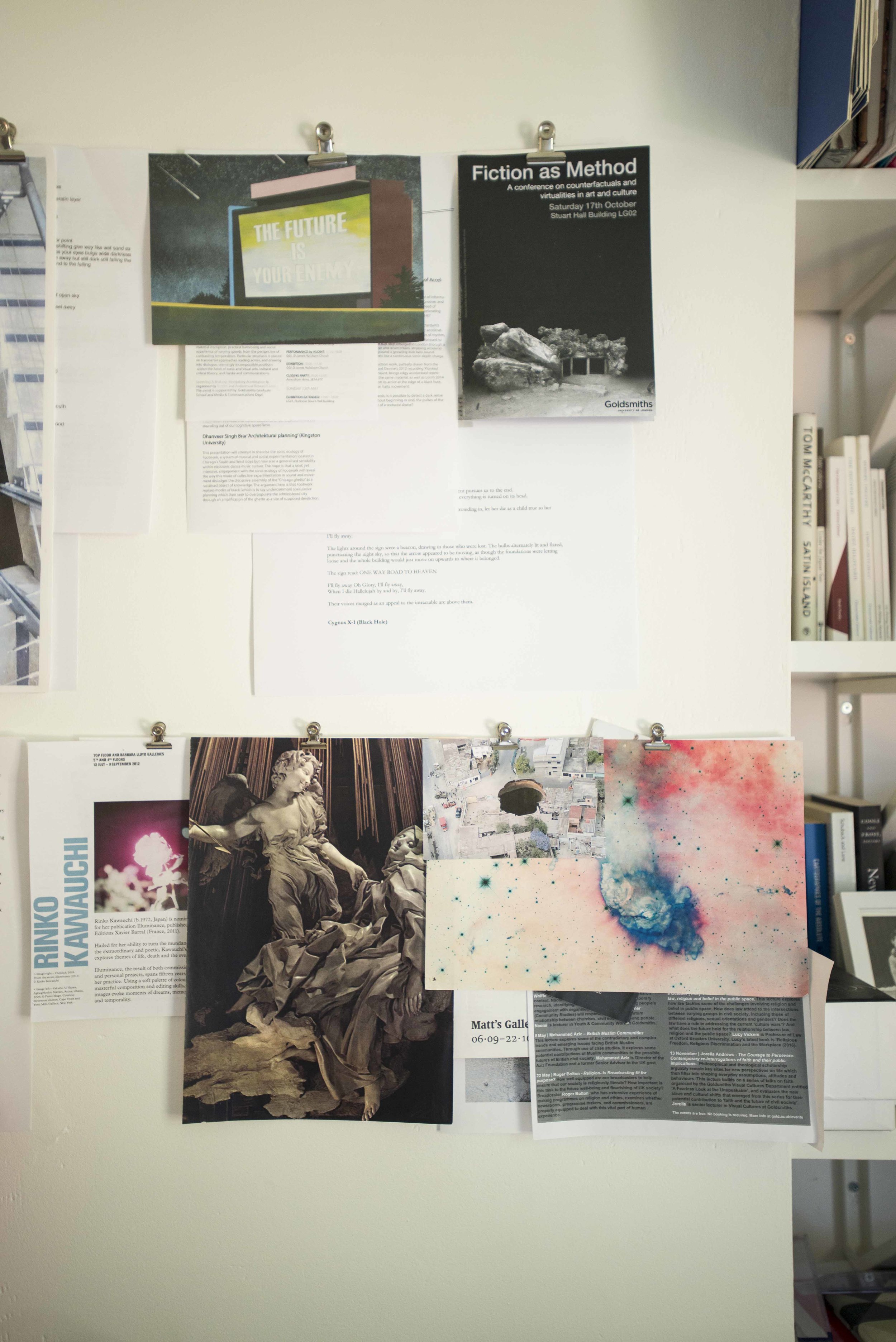

And this is not Kate preaching out loud her believes, but she does play with it in her work. “For a long time, I’ve been making work around questions about faith and belief. About the anomaly of being a christian in the art world”. Kate’s work goes around creating texts about her research’s adopting fiction and experimental theories. She sometimes involves movement in her performative readings.

Kate's MFA final degree exhibition, ‘Untitled’, was a screening of a scripted performance playing on ideas of the threat of religious fundamentalism. She enacted an artist who displays a progressively zealous and religious aspect to her description of her artistic practice, finally labelling it 'the truth'.

Seems like believing in organised religion goes beyond the pale for some people. And it’s not that Kate regrets working about these subjects, but she is now more conscious of how many doors have been closed because of it. "I think my degree show was good, but I thought it was a terrible idea in relation to my career because I shot myself in the foot. I was not invited to any exhibitions initially after my degree show because the performance made people feel uncomfortable", explains Kate to me of what happened to her after graduating from her master in Fine Art Practice Goldsmith in 2009.

Ironically, art and religion were almost completely embedded to one practice in the 15th and 16th century. As a Guardian article says, from the dark ages to the end of the 17th century, the vast majority of artistic commissions in Europe were religious. Kate’s career would have probably been much more accepted then. Ileana Tu, an art curator from Taiwan, on the other side says that it’s not that art discriminates religion, but that art should let people think, reflect rather than complain. It should take the form of a philosophy term.

“I gave up thinking that people would like my work”

(In relation to her past work)

As part of her PhD proposal, Kate is currently working on a project around megachurches, places where there are 2000 or more people attending a religious service.. She is particularly interested in the way that site, spectacle and narrative works within the church group. Her interdisciplinary, practice-based project, seeks to understand the orienting appeal of Evangelicalism within a 'post-truth' political climate. Her next short term future plans are to go to Lakewood Church in Houston, Texas, currently America's largest megachurch. For her, these megachurches are quite boundaried in relation to behaviour. They have different norms and assumptions to secular environments.

Kate no longer considers herself an evangelical and attends church occasionally for research purposes. She believes it is important however to keep an open balanced mind when visiting megachurches and not approach them cynically.